Venice is full of secrets, hidden stories and Venice curiosities that even many locals don’t know. Beyond the famous canals and iconic landmarks, the city hides centuries of inventions, unusual traditions, architectural tricks and small details that reveal a completely different story — the real Venice.

This page gathers true, verified curiosities that reveal how ingenious, creative and surprising Venetian life has always been.

From the world’s first patent law to ancient rain-filtering wells to numbers that go up to 5,000, each fact opens a window onto a quieter, smarter and more authentic Venice.

If you love discovering what other visitors miss, you’re in the right place.

Here are Venice’s most fascinating hidden facts — explained simply, clearly, and with the touch of a local.

⭐ Explore Venice’s Most Fascinating Curiosities (start here)

Venice hides extraordinary inventions, unique laws, and surprising stories that shaped the modern world.

If you don’t want to scroll through the entire page, start from these major discoveries.

🧠 Venice Changed the World

👉 📜 Venice Invented the First Patent Law (1474) — the origin of modern intellectual property and innovation systems.

👉 🦠 Venice Invented the World’s First Quarantine (1423) — the revolutionary health system that saved millions of lives worldwide.

👉 👓 The First Eyeglasses in History Were Born in Venice — a Venetian invention that transformed reading and knowledge.

👉 🎼 The First Printed Polyphonic Music (1501) — Venice made music accessible across Europe.

👉 🎰 The World’s First Casino Was Born in Venice (1638) — the beginning of regulated public gambling.

🏛️ Power, Society & Identity of Venice

👉 👑 The Doge of Venice — Not a King, But a Servant of the Republic

👉 ✡️ The Venetian Ghetto — The World’s First Ghetto (1516)

🔎 👇 Or scroll down to explore all hidden Venice curiosities and hidden details. ↓

This page collects dozens of lesser-known details about Venice’s architecture, traditions, engineering, and everyday life.

Venice Curiosities: The Stories Behind the City’s Hidden Details

👑 The Doge Was Not a King — And He Could Not Be Rich

Many visitors imagine the Doge as a powerful king ruling Venice with unlimited wealth.

The truth is the opposite.

The Doge was chosen among noble families, but the moment he took office, he became a servant of the Republic, not a monarch.

He was strictly controlled:

- he could not accept gifts

- he could not trade or do business

- he could not use his position for his family

- he had to ask approval for many personal expenses

- after his death, his assets were inspected to ensure he gained nothing illegally

The Doge lived with dignity, but not in luxury — his palace was grand for diplomatic reasons, not personal comfort.

This system ensured that Venice was ruled “for the good of the city,” not for personal power.

It’s one of the reasons the Venetian Republic lasted over 1,000 years.

👉 To learn even more about his role, duties, and how the office shaped Venetian history, read THE DOGE OF VENICE

👉 To understand how the Republic ended and Venice fell to Napoleon, read Ludovico Manin, the Last Doge of Venice

🦁 The Winged Lion of Venice — The Symbol That Defined a Republic

The Winged Lion of Venice is everywhere: on palaces, bridges, old gates, ancient coins, gondolas, even on the flags that still fly across the lagoon. But few visitors know how deep its meaning truly is. This majestic creature represents Saint Mark, Venice’s patron, and carries the ideals that shaped the Republic for more than 1,000 years.

Every detail hides a message: the wings symbolize divine inspiration, the open book stands for wisdom and peace, the sword represents justice, and the halo marks the sacred role Venice believed it held in the world. Wherever the Republic ruled — from the Aegean islands to the Adriatic ports — the lion followed, carved into stone as a sign of authority and protection.

Understanding this symbol changes how you see the city: Venice wasn’t just beautiful — it was a civilisation with its own identity, laws and values, all condensed into the figure of a winged lion watching over its people.

👉 Discover the full story here: 🦁 The Winged Lion of Venice — The Symbol That Defines a City

📜 Venice Invented the First Patent Law (1474)

Few visitors know this: the world’s first modern patent law was created in Venice.

In 1474, the Republic issued a revolutionary decree stating that anyone who invented a device or technique “not previously made in our dominion” would receive exclusive rights for 10 years.

This law protected glassmakers, shipbuilders, engineers, printers and artisans from imitation — giving Venice a massive technological advantage.

It’s considered the ancestor of the patent systems used worldwide today.

A global legal concept was born right here in the lagoon.

👉 To learn more, read also the page 🧠 Venice Invented the First Patent Law (1474)

👓 Venice Invented the First Modern Eyeglasses (1300s)

Long before sunglasses were made in Murano, Venice had already changed the world with another invention: the first wearable eyeglasses.

Between the late 1200s and early 1300s, Venetian glassmakers created the earliest known spectacles, made with two round lenses joined by a simple frame that rested on the nose.

These pioneering glasses helped monks read, allowed craftsmen to continue working as they aged, and quickly spread across Europe.

It was a quiet revolution — and it began in the workshops of Venetian artisans.

Discover 👓 The First Eyeglasses in History Were Born in Venice

👓 Murano Made the First Colored “Sunglasses”

As early as the 1500s, Murano glassmakers were producing:

- lightly tinted lenses

- dark lenses to reduce glare

- green and blue filters used by fishermen

- protective shades for long hours in sunlight

The intense reflection of the Venetian lagoon pushed artisans to experiment with special pigments and techniques.

These creations are considered by many historians to be the first sunglasses in history.

Centuries before fashion houses existed, Murano was already innovating eyewear.

👉 learn more about ✨Murano Island Venice — What to See + How to Visit

Among the most surprising curiosities of Venice, this one is often unknown even to Italians:

👋 “Ciao” Was Born in Venice

One of the most surprising Venetian curiosities is that the world-famous word “ciao” is widely believed to have originated in Venice.

Its origin comes from the old Venetian expression “sciavo vostro”, meaning “your servant” or “at your service”. It wasn’t meant literally — it was a polite, friendly greeting used in everyday lagoon life.

Over the centuries, s’ciavo softened into “ciao”, losing its original meaning and becoming a warm, universal way to say both hello and goodbye.

Today ciao is one of the most recognized Italian words worldwide, spoken in cafés in New York, beaches in Australia, and even in pop culture — yet its story begins right here in Venice, among narrow calli, stone bridges, and lagoon traditions.

A global greeting, born from a local heart.

🔴 The Pittima — Venice’s Public Debt Enforcer

One of the most unusual figures in Venetian history was the pittima, a person legally appointed to pressure debtors into paying what they owed.

The pittima would follow the debtor everywhere — in the streets, in public spaces, even outside their home or workplace — constantly reminding them of the unpaid debt and attracting public attention. The goal was social pressure and public embarrassment rather than physical punishment.

To ensure visibility, the pittima was dressed in distinctive clothing, often red, so that everyone could immediately recognise the situation.

Acting under legal authority, the pittima could not be removed or attacked. Interfering with her meant violating the law.

This unusual practice reveals how the Venetian Republic relied not only on courts and contracts, but also on public reputation and social pressure to enforce economic obligations.

Not all Venetian details are centuries-old wonders — some are simple, charming pieces of daily life.

🛴 When History Becomes Everyday Life

This curved iron structure wasn’t originally a window grate.

In the past, similar corner guards helped protect fragile brick walls from carts, deliveries, or bumps in Venice’s narrow calli.

Today, it serves a completely new purpose:

a scooter rack for local children.

A creative reuse of old ironwork, and a perfect example of how Venice quietly transforms its historic details into modern and practical solutions.

📘 Venice Printed the First Modern Books

Few visitors know that Venice was once the Silicon Valley of printing. In the late 1400s, the city became the most advanced publishing center in Europe, attracting scholars, travelers and innovators from every corner of the continent.

Here, Aldus Manutius created a revolution that changed how the world reads: small, portable books that anyone could carry — the ancestors of today’s paperbacks. He also invented italic type and introduced affordable editions of the classics, making knowledge accessible for the first time.

Venice’s printing houses produced thousands of titles in dozens of languages, spreading ideas faster than ever before. The Renaissance spread across Europe thanks to these Venetian workshops of ink, paper and genius.

👉 To learn more, read also the page 📘 Venice and the Birth of Printed Books (1469)

🧵 “Punto Burano”: Lace More Valuable Than Gold

The lace of Burano, produced entirely by hand with a needle, became one of Europe’s most luxurious crafts between the 1500s and 1700s.

Every piece required months of work, thread by thread, using techniques passed down from mother to daughter.

Burano lace was so precious that:

- Queens and nobles competed to buy it

- It was exported across all major European courts

- a single collar could cost as much as a small house

Today, lacemakers still keep this extraordinary art alive in the island’s workshops.

👉 learn more about 🌈 Burano – The Island of Colors and Tradition

🎼 Venice Printed the First Polyphonic Music (1501)

Before Venice became famous for gondolas and canals, it led a quieter revolution: the invention of printed music.

In 1501, Ottaviano Petrucci published the Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, the first collection of polyphonic music ever printed. Until that moment, music spread slowly through handwritten manuscripts — rare, fragile and expensive.

Petrucci solved a problem musicians had faced for centuries: how to share complex compositions accurately and efficiently. Venice’s printing presses allowed music to travel across Europe, connecting choirs, cathedrals and courts. Many historians consider this moment the birth of modern music publishing.

👉 To learn more, read also the page 🎼 The First Printed Polyphonic Music (1501)

🚣 The Gondola Is Asymmetrical — Because It’s Tailor-Made

A gondola is not symmetrical.

The left side is wider by about 24 cm so the boat can move straight while the gondolier rows on one side.

But there is something even more fascinating: each gondola is custom-built for its gondolier.

Craftsmen adjust:

- width

- curvature

- balance

- height of the oarlock

- weight distribution

based on the gondolier’s height, weight, rowing style and dominant arm.

Every gondola is a unique instrument built around the person who will use it — a floating example of Venetian precision craftsmanship.

⚫ Why All Gondolas Are Black

In the 1500s, gondolas were decorated with bright colors, precious fabrics and even gold.

It became a competition of wealth among noble families.

To stop the excess, the Republic issued a law:

all gondolas must be painted black.

The colour signified elegance, uniformity, and reduced extravagance.

This law is still respected today, giving Venice one of its most iconic symbols.

🪢 The “Forcola”: A Sculpted Engine of Wooden Engineering

The forcola is the distinctive oarlock used on gondolas and other traditional Venetian boats.

It looks like a piece of wooden art — and it is.

Carved from a single block of walnut, each forcola:

- is completely handmade

- has multiple curves allowing different rowing positions

- lets the gondolier brake, turn, accelerate and maneuver with one single oar

- is shaped based on the gondolier’s posture and technique

No two forcole are identical.

They are functional sculptures, combining art and engineering in pure Venetian style.

🌬️ Venetian Chimneys Were Designed to Stop Fires

Venice’s chimneys have unique shapes — like hats, domes or mushrooms — and they are found nowhere else in the world.

They were engineered to:

- block sparks from rising

- prevent wind from forcing smoke back inside

- resist rain

- reduce the risk of fire in a city historically built in wood

Every sestiere developed its own style, and many chimneys you see today still use 500-year-old designs.

A perfect mix of beauty and function.

To learn more about venetian chimneys, visit 🌬️ Venetian Chimneys: The Ingenious Fire-Stopping Towers of Venice

🌄 Altane: Rooftop Terraces for Sun-Bleaching Hair

Altane are small wooden terraces perched on Venetian rooftops.

Originally, they served a very particular purpose: bleaching hair with sunlight.

In the Renaissance, women prepared mixtures of herbs, soda or vinegar and sat under the sun with open-top hats, letting the light naturally lighten their hair.

Altane were also used to dry laundry, ventilate homes and enjoy fresh air far from the humidity of the ground level.

They remain one of the most charming — and least known — features of Venetian architecture.

👉 See the full page 🌞 Altane of Venice — The Secret Rooftop Terraces Above the City

🧱 Fondamente: Walkways Built on Visible Foundations

A fondamenta is a walkway along a canal, but the name comes from something deeper:

the term refers to the visible foundations of buildings.

Venice is built on thousands of wooden piles.

Along many fondamenta you can still see portions of these ancient structures, showing how the city literally rises from the water.

Fondamente are perfect for peaceful walks, photography and observing everyday Venetian life up close.

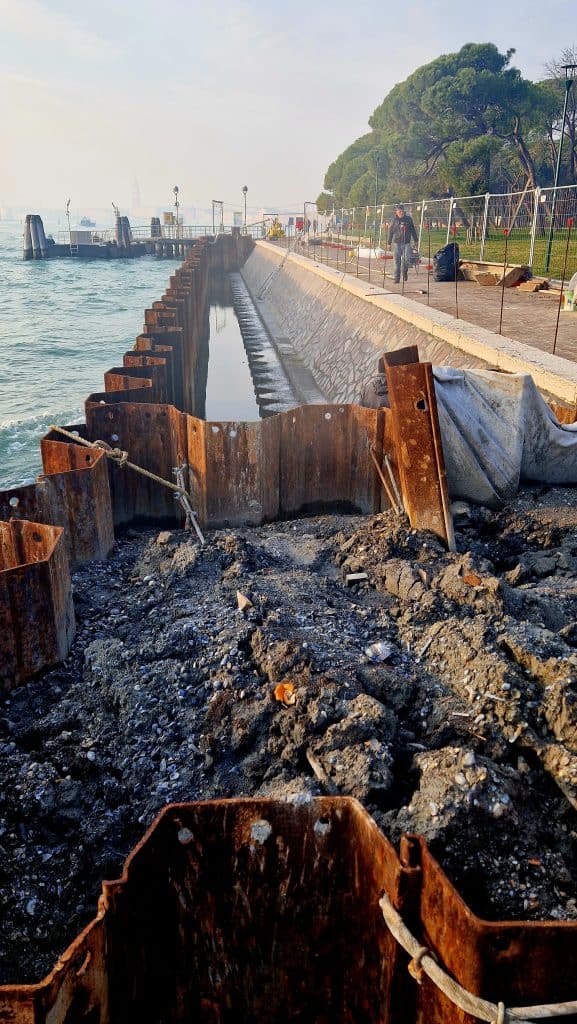

🔧 How Venice repairs its foundations

Venice constantly fights the sea to survive. In this photo you see a major hydraulic engineering intervention: a cofferdam built with interlocking steel sheet piles (palancole).

These metal panels are driven into the lagoon bed to form a watertight barrier. Once sealed, water inside the enclosed area is pumped out, creating a dry workspace below sea level.

This allows workers to repair or reinforce the stone embankments and foundations of the city — literally working on Venice’s “fondamenta” in the truest sense of the word.

The dark sediment in the foreground is lagoon mud removed during excavation, often filled with shells and centuries of accumulated deposits.

🛠️ This is just one example of how Venice survives thanks to engineering

What you see here is not an isolated case.

Venice has been shaped — and constantly repaired — through centuries of hydraulic engineering, canal works, coastal barriers and interventions on the lagoon itself.

If you want to understand how Venice is really managed and protected, you can continue here: 👉 🌊 Engineering the Lagoon — How Venice Learned to Control Water

✨ Terrazzo Flooring in Venice — Venice’s Most Durable Artistic Invention

Terrazzo might look like polished stone, but it was one of Venice’s smartest architectural solutions. Instead of wasting precious marble scraps, artisans mixed tiny chips with lime, pressed everything together, and polished it until it shone like a single smooth surface. The result was elegant, affordable, and extremely durable — perfect for palaces, scuole and theatres. Many floors you walk on today are the same ones laid centuries ago, still glowing under the light.

👉 Discover the full story: ✨ Terrazzo Flooring in Venice – The Art and Magic of Venetian Terrazzo Floors

🧩 Curiosity: the ‘old Campo San Paternian’ under your feet (today Campo Manin)

Right next to the monument, look down: there’s a stone/map plaque that reads “Campo S. Paternian e adiacenze prima degli interventi del XIX secolo”. It’s a quiet reminder that this area wasn’t always shaped like today—parts of central Venice were reworked in the 19th century, and this little “floor map” preserves the memory of the earlier layout.

🎰 The World’s First Casino Was Born in Venice

In 1638, Venice established the first publicly regulated, state-controlled casino, giving formal structure to an activity that already existed elsewhere in less organized forms. These “ridotti” were elegant rooms where nobles, travelers and diplomats gathered to play cards, listen to music, and enjoy masked evenings governed by strict rules. Masks were even mandatory — anonymity encouraged bold play and protected reputations. What began as a Venetian experiment became the foundation of the modern casino we know today.

👉 Learn more here: 🎰 The World’s First Casino Was Born in Venice – The Ridotto of 1638

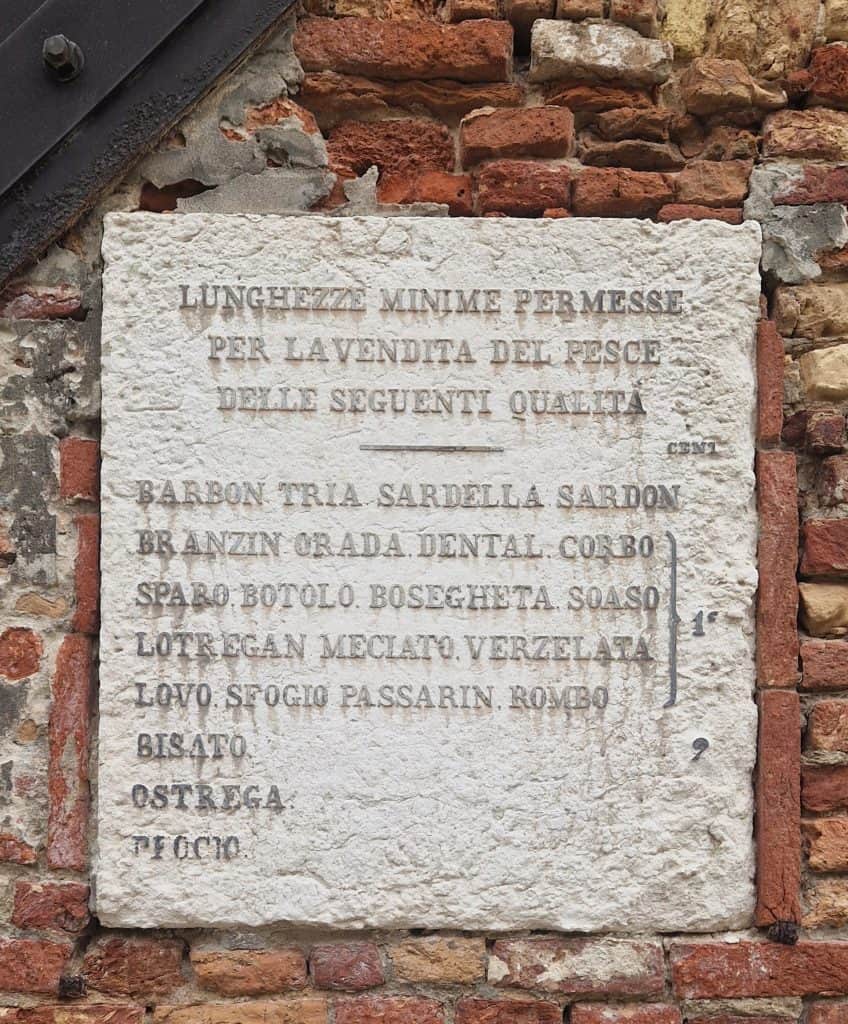

🎣 Venice’s Ancient Fish-Size Laws: The Early Eco Rules You Can Still See on the Walls

Across Venice you can still spot old stone plaques listing the minimum legal size of fish allowed for sale.

These rules are far older than the plaques themselves: they go back to the time of the Venetian Republic, when the lagoon’s resources were tightly protected.

🕰️ Originally Written in Ancient Venetian Units

The earliest versions of these regulations were expressed using traditional Venetian measures such as:

- piede veneziano (Venetian foot)

- oncia (ounce)

- quarto (quarter unit)

Fish sellers at Rialto had to follow these exact sizes, and inspectors checked the catch daily to prevent overfishing.

The idea was simple but revolutionary for its time:

👉 protect young fish so the lagoon could regenerate

👉 avoid depletion of vital species

👉 maintain a sustainable food supply for the city

In other words: early environmental management, 400 years before “ecology” became a word.

To learn more about Venetian units, visit 📐 Misure Veneziane – The Old Venetian Units of Measurement

📏 Why Some Plaques Now Show Centimeters

The plaque in the photo is a later version — probably from the Napoleonic or early Austrian period — when Venice adopted the metric system.

That is why the species list is followed by sizes in centimeters, not in piedi or once.

This makes the plaque historically fascinating:

it preserves an ancient Venetian rule, but written using a modern measurement system imposed by foreign administrations.

It’s a rare example of how Venice’s centuries-old laws adapted while the rest of the political world changed around them.

🌊 A Hidden Treasure of Lagoon History

Each plaque, whether marked in ancient Venetian units or modern centimeters, reflects the same idea:

Venice always treated its lagoon as a living, fragile ecosystem to protect — not to exploit.

Most visitors walk past these stones without knowing what they mean, but they are among the most revealing details of Venice’s long, intelligent relationship with nature.

💧 Venetian Wells Were Ingenious Rain Filters

Venice has no natural freshwater sources.

So the wells you see in campi and courtyards are not traditional wells — they never reached groundwater.

Instead, they collected rainwater, filtered naturally through layers of sand placed beneath the square.

The water then accumulated in a sealed cistern, kept cool and clean.

For centuries, this system provided safe drinking water to the entire population.

A brilliant example of medieval engineering designed for life on the lagoon.

Read also 💧 Venetian Wells: The Hidden Water System That Kept Venice Alive

🚰 Public Fountains: Venice’s Modern “Nasone”

Because Venice still has no freshwater springs, the city installed modern fountains — simple metal spouts you’ll see in campi, along fondamenta and near vaporetto stops.

These fountains provide:

- clean, drinkable water

- completely free

- perfect refreshment during hot days

Locals use them daily, and visitors often overlook them — but they are one of Venice’s best resources for exploring the city with a refillable bottle.

🦠 Venice Invented the World’s First Quarantine (1423)

Long before modern medicine, Venice faced waves of plague arriving on merchant ships. Unlike other cities, the Republic created something completely new: an organized system of quarantine.

In 1423, the island of Lazzaretto Vecchio became the world’s first official quarantine station, where arrivals were isolated for quaranta giorni — forty days — to prevent the disease from spreading.

The system was shockingly advanced for its time: doctors, inspections, isolation protocols, and even early forms of sanitation. This Venetian invention saved countless lives and became the model used worldwide for centuries.

The word “quarantine” itself was born here, in the lagoon.

👉 To learn more, read also the page 🦠 Venice Invented the World’s First Quarantine (1423)

❤️ Venice Had Legal Prostitution — And Women Were Protected by Law

Few visitors know that prostitution was legal and regulated in Venice for centuries.

From the Middle Ages, the Venetian Republic officially authorized brothels, especially in areas like Castelletto near Rialto. The government saw prostitution as a social reality to manage — not hide — and created strict rules to control the activity.

Authorities established:

- licensed areas where prostitution was permitted

- taxes paid to the state

- rules to prevent disorder and violence

- legal protection for the women

What surprises many visitors is this: harming a prostitute was considered a serious crime.

Violence against them could lead to heavy punishment, because the Republic viewed them as workers under state protection. Their safety was part of public order.

Venice approached the issue with typical pragmatism: regulation instead of prohibition, control instead of chaos.

This system reveals another side of Venetian society — practical, organized, and often far more modern than we imagine.

🚢 The Zattere: Venice’s Floating “Highway of Goods”

The long promenade known as Zattere takes its name from the enormous wooden rafts — true floating platforms, not simple boats — that once docked here every day.

These zattere carried everything Venice depended on: wood for heating, stone for palaces, salt for preservation, wine, coal, fabrics, and even livestock. Because of their massive size, they needed several expert boatmen to steer them through the lagoon.

Knowing this transforms the peaceful Zattere you see today: it was once one of the busiest commercial hubs of the entire Republic, a constant flow of movement and noise bringing life into the city.

🎭 The Commedia dell’Arte in Venice

Born on the stages of Renaissance Italy, the Commedia dell’Arte became one of Venice’s most vibrant cultural expressions.

Improvised dialogues, quick wit, and iconic masks gave life to characters like Arlecchino, Colombina, and Pantalone, who still influence theatre, fashion, and Carnival traditions today.

Discover how these travelling actors shaped Venetian humour and left a legacy that continues to inspire performers around the world.

👉 Read more: 🎭 Commedia dell’Arte: Venice and the Birth of Italian Theatre

🏛️ The Venetian Fonteghi — Medieval Warehouses That Worked Like Today’s Freeports

Few visitors realise that Venice once had a network of fonteghi: special state-controlled warehouses where foreign merchants were required to store their goods.

These buildings acted as customs hubs, financial centres, and supervised markets all in one.

Inside, officials inspected merchandise, collected taxes, and monitored trade to ensure fairness and avoid smuggling.

The most famous were:

- the Fontego dei Tedeschi, for German merchants;

- the Fontego dei Turchi, for traders from the Ottoman Empire;

- the Fontego dei Persiani, for merchants from Persia (now lost).

Merchants were obliged to live and conduct business inside the fontego for a set number of days. This allowed Venice to regulate every aspect of international trade — prices, quantities, and even negotiations.

It was a system centuries ahead of its time: part customs house, part embassy, part bank.

👉 To explore the history, architecture, and role of these unique buildings, read the full guide: 🏛️ Venetian Fonteghi: The Trading Hubs That Powered a Global Empire

🛡️ Venice Created the First Maritime Insurance System

During the Middle Ages, sailing was dangerous — storms, pirates and shipwrecks were common. Venice solved this with another world first: maritime insurance.

Merchants could share risks, protect cargo, and recover losses if their goods never arrived. These early contracts, recorded in the State Archives, read astonishingly similar to modern insurance policies.

This innovation helped Venetian merchants dominate Mediterranean trade, making shipping safer, more predictable, and far more profitable. It’s one of the financial pillars that allowed the Republic to prosper for nearly a thousand years.

👉 To learn more, read also the page ⚓ Venice Maritime Insurance History — How Venice Invented Modern Sea Insurance

🧩 The Secret Trading Codes Carved Into the Stone

Along certain fondamenta — especially in Dorsoduro and Castello — you can still spot small carved symbols: circles, crosses, geometric marks.

These were the merchants’ secret markings, a kind of medieval logistic system.

Before house numbers existed, they indicated:

- exact loading and unloading points

- ownership of warehouses

- routes and instructions for boatmen

- goods that required care or protection

They were the lagoon’s first barcodes, invisible to today’s tourists but essential in keeping Venice’s commercial network running smoothly.

Finding them means looking at the city through the eyes of its merchants and boat workers.

🎨 The Arsenale’s Color Codes: A Medieval Badge System

During its peak, the Arsenale was Europe’s largest industrial complex, with thousands of workers — carpenters, blacksmiths, rope-makers, sail-makers, caulkers — all operating simultaneously.

To coordinate this enormous workforce, the Republic developed an ingenious organizational system: each trade had its own color and symbol, each gate carried an emblem, and entrances were controlled visually.

This created a form of medieval ID badge system, long before modern industry existed.

It is one of the reasons Venice could build a fully equipped warship in record time.

⛵ Venice Invented the First Scheduled Passenger Ships

Centuries before buses or trains existed, Venice created the galea da mercato — the world’s first scheduled passenger service.

These ships followed fixed routes and fixed dates, taking merchants, pilgrims and diplomats from Venice to Constantinople, Alexandria, Flanders and beyond.

Timetables were regulated by the government, and passage was open to anyone who could pay — a remarkably modern concept.

This system made travel predictable and safe, helping Venice connect the Mediterranean long before the idea of “public transport” was born.

🚪 Water Doors: The True Main Entrances of Venetian Homes

Most Venetian palaces were designed with their primary entrance facing the canal, not the street.

These water doors were large, elegant, and richly decorated — because guests, ambassadors, and merchants arrived by boat.

The smaller door on the land side was merely a secondary access.

Understanding this completely changes the way you see Venetian architecture: the façades that appear simple from the street become masterpieces when viewed from the water, exactly as intended.

🌊 Why Many Venetian Doors Are Raised Above the Ground

Walk through Venice and you’ll notice something unusual: thousands of doors sit 20 to 40 centimeters above street level, with a step you must climb before entering.

This wasn’t poor construction — it was a deliberate design choice created by people who understood the lagoon better than anyone.

For centuries, Venice lived with frequent minor floods, long before modern barriers existed. Rainwater, high tides, and boat movement could easily spill into the calli. To protect homes, Venetians elevated their doors so that:

- rising water couldn’t enter the house

- trash and floating debris stayed out

- humidity was reduced at ground level

It was an early, brilliant form of flood defense, built into everyday architecture.

These raised thresholds are a perfect example of how Venetians turned their environment into engineering — adapting every house to the rhythm of the tides.

🎭 Venice Invented the Modern Stage Curtain System

In the 1600s, Venice wasn’t just a maritime powerhouse — it was the theatre capital of Europe.

The city had more than 18 active public theatres, an unimaginable number for the time.

Here, Venetian engineers and scenographers invented the systems that shaped modern theatre.

Venice pioneered:

- the sliding stage curtain (sipario scorrevole)

- rotating scenic panels

- multi-layer backdrops

- early special effects using ropes and counterweights

Before Venice, curtains were simple drapes lifted manually.

Venetians transformed them into a mechanical system, allowing smooth openings, dramatic reveals, and complex scene changes — all controlled with hidden machinery backstage.

This innovation spread to Paris, London, Vienna and became the international standard.

Every time a curtain rises in a theatre today, the mechanism behind it can be traced back to the inventive spirit of Renaissance Venice.

🪟 Why So Many Venetian Windows Are Bricked Up

As you wander through Venice, you’ll spot many windows that appear… “ghost-like.”

Perfectly filled with bricks. Same frame, same shape — but no glass, no opening.

Why?

There are several fascinating reasons, depending on the century:

🧾 Window taxes: some periods of Venetian history taxed homes based on the number of windows. Bricking one up reduced your tax bill.

🪨 Structural reinforcement: adding bricks strengthened walls against humidity, saltwater erosion, and shifting foundations.

🥶 Protection from cold drafts: old Venetian winters were harsh, and sealing a window made houses warmer.

👀 Privacy in narrow calli: some windows looked directly into neighbors’ homes — closing them was the easiest solution.

What makes these “ghost windows” unique is that Venetians usually kept the original frame for aesthetic harmony.

So the façade of the building stayed beautiful and balanced, even if the window behind it no longer existed.

Today, bricked windows are a silent record of Venice’s battle with economics, climate, and architectural survival — small clues of the city’s past, hidden in plain sight.

🐾 Wellheads With “Anti-Crime” Symbols

Venice’s famous vere da pozzo — the stone wellheads found in campi and courtyards — often display carved animals, flowers, or decorative symbols.

But these carvings served practical purposes.

They indicated:

- whether water was safe to drink

- whether access was restricted

- ownership by a Scuola or noble family

- rules for water distribution

In a city that relied on filtered rainwater, these symbols worked as medieval regulatory signs, helping prevent misuse, disputes, and theft of precious drinking water.

⚰️ The “Doors of the Dead”: A Quiet Remnant of Venetian Tradition

On some older buildings, you may notice a small doorway, now sealed, close to ground level.

These are porte dei morti — “doors of the dead.”

Traditionally, the deceased were carried out through this secondary door to preserve the symbolic purity of the main entrance.

These discreet openings are among the most intimate and touching traces of domestic life in historic Venice, rarely recognized by visitors but deeply meaningful to those who know their purpose.

🪝 Medieval Boat Hooks Still Embedded in the Walls

In many narrow canals or waterfront alleys, rusty iron hooks or rings still protrude from the walls.

These were mooring hooks used between the 1300s and 1500s for:

- tying small boats

- securing cargo rafts

- stabilizing fishing vessels

- unloading goods safely

They show that Venice wasn’t just a city with a port — the entire city was the port.

Every corner of the lagoon once had a practical, working function.

🐟 The Hidden Fish Tanks of Old Courtyards

Some campielli and private courtyards contain strange square holes or stone grates.

These were pesiere — stone tanks used to keep fish alive before sale.

Fresh fish was stored in circulating water and sold only when needed, ensuring perfect freshness.

Finding one of these ancient tanks is like discovering a forgotten piece of Venice’s everyday food culture.

🏚 Crooked Houses Are Not Sinking — They Are Adapted

Visitors often assume that leaning or crooked Venetian houses are the result of subsidence.

But many of these structures are intentionally shaped to:

- follow the irregular line of ancient alleys

- connect with older walls already in place

- maximize living space above narrow streets

- adapt to uneven foundations

- respect historical property boundaries

Venice grew organically over centuries, adjusting itself to every available angle.

These crooked façades are not flaws — they’re part of Venice’s adaptive architecture.

🐴 The Mushroom-Shaped Stones for Tying Horses

Before boats dominated transportation, several Venetian islands kept horses for carrying loads or agricultural work.

The small mushroom-shaped stones found in certain campi were tie-posts for horses.

Travelers would loop reins around them the same way sailors tied their ropes.

Today they look like decorative relics, but they reveal a forgotten chapter of the lagoon’s mixed land-and-water life.

🕯️ Venice’s Street Shrines: The City’s Open-Air “Guardians”

All around Venice you’ll notice small religious shrines built directly into the walls of houses — tiny balconies with flowers, candles and a saint watching over the calle.

They are called edicole votive, and they are one of the most authentic symbols of Venetian everyday life.

💬 In Venetian dialect these shrines are affectionately called capitèi, a word still used by locals today.

These shrines were not just decorations. For centuries they served three essential purposes:

🛡️ 1. Protection and Gratitude

Families, guilds or even entire “contrade” (micro-neighborhoods) built these shrines to thank a saint for protection during epidemics, wars, fires or difficult times.

Many plaques read “Gli abitanti di questa contrada riconoscenti…” — a collective gesture of gratitude.

The photo belongs exactly to this tradition:

💬 “Gli abitanti di questa contrada riconoscenti – Guerra 1940–45”

A touching reminder of how Venetians rebuilt hope after World War II.

🔦 2. Lighting the Streets Before Electricity

These shrines once had real oil lamps inside.

Before streetlights existed, Venice’s labyrinth of alleys could be terrifyingly dark — and dangerous.

Shrines acted as public lanterns, guiding people at night and reducing crime.

They were literally the city’s first street lights.

🎭 3. Identity Markers of Each Neighborhood

Every shrine has a different style:

- simple wooden boxes,

- stone niches,

- elaborate miniature altars,

- ironwork balconies with flowers.

They show the personality of each area: Castello’s humble shrines, Cannaregio’s colorful ones, San Polo’s older stone niches, and so on.

Locals still keep them clean and decorated with fresh flowers — a silent proof that Venice is alive.

📸 A Hidden Gem for Photographers

Most visitors don’t even notice these shrines, but once you see one, you’ll start spotting them everywhere.

They are some of the most photogenic details in Venice — especially when candles are lit in the evening.

🌊 Water Marks on Old Doors: Natural Records of the Tides

Many ground-floor doors show dark lines, mineral streaks, or salt deposits.

These are porte segnate — natural records of past tide levels.

Each acqua alta left:

- algae

- silt

- minerals

- salt

forming layers that built up over decades.

These silent marks create one of the most poetic “archives” in Venice: a visual diary of the lagoon’s history, written directly on the city’s doors.

🧱 Barbacani — The Mysterious Beams That Shaped Venice’s Streets

These wooden or stone brackets sticking out from buildings are called barbacani.

They look decorative, but they were extremely important.

Historically, barbacani served to:

- expand living space above narrow streets

- define legal boundaries between one property and the next

They also functioned as a rule:

👉 you could extend your house only as far as your barbacane allowed — without touching the neighbor’s.

They shaped the silhouette of many calli and explain why upper floors in Venice often appear wider than the street below.

🔢 House Numbers Reach 5,000 — and Don’t Follow Streets

Venice does not number houses street by street.

Each sestiere has its own continuous numbering system, sometimes running into the thousands.

For example:

Castello → numbers up to ~5,000

Cannaregio → over 6,000

Other sestieri → similar spiraling numbering

An address like Castello 4541/A simply means house 4541 in the district of Castello — not on a specific “street”.

It’s confusing at first, but it reflects Venice’s ancient administrative system

🪵 Venice Is Built on Millions of Wooden Piles That Don’t Rot

It sounds impossible, but the entire city stands on millions of wooden piles driven deep into the lagoon’s muddy seabed.

The secret is that these piles — often made of alder, larch or oak — do not rot.

Why?

They are completely submerged in oxygen-free water, so bacteria cannot grow

Over centuries, minerals in the water slowly petrify the wood

The piles become hard like stone and fuse with the sediment

This creates an extremely stable base for the city

This natural “underwater preservation” is one of the reasons Venice’s oldest buildings, from palaces to churches, are still perfectly standing after 800 years.

Venice doesn’t float — it rests on millions of natural pillars that science once struggled to explain.

Curious how Venice really stands on water? Discover how Venice wooden piles and foundations support the entire city.

🕍 The First Ghetto in History Was Born in Venice

Hidden in the district of Cannaregio lies one of the most important places in world history: the very first ghetto, established in Venice in 1516.

The word ghetto itself comes from the Venetian term geto (pronounced “jetto”), meaning foundry, because the area had once been used to cast metal. When the Republic designated this zone as the segregated district for the Jewish community, the name of the foundry became the name of the district — and eventually spread across the world.

Life in the Venetian Ghetto was highly regulated.

At sunset, guards closed the heavy gates and patrolled the bridges; at dawn, the gates reopened. The Jewish community was required to live inside the district, but during the day they were free to work, trade, teach, print books or practice professions that Venice valued.

Despite the restrictions, the Ghetto became a thriving cultural center, known for:

- some of Europe’s earliest Hebrew printing presses

- schools of philosophy and music

- merchants who traded across the Mediterranean

- communities speaking five different languages

Because space was limited and the population grew, buildings were constructed upward, creating some of the tallest residential houses in Venice, with narrow windows and stacked floors that still define the Ghetto’s unique silhouette today.

Visiting the area reveals something extraordinary:

it is not only a place of segregation and hardship, but also a place of resilience, creativity and cultural brilliance. The Venetian Ghetto shaped history far beyond the lagoon — it created a word and a concept that would echo for centuries.

To learn more about the Ghetto, visit 🔯 THE VENETIAN GHETTO — The World’s First Ghetto (1516)

🌬️ Narrow Streets Create a “Wind Channel” Effect

Some of Venice’s narrowest calli create a curious natural phenomenon:

a Venturi effect, where wind accelerates when passing through tight spaces.

Locals notice it especially in summer:

the air feels cooler

the breeze becomes stronger

humidity temporarily drops

walking becomes more comfortable

This micro-climate effect is so real that Venetians will sometimes choose a narrower path specifically to “cool down.”

It’s one of those tiny daily details that make the city’s layout surprisingly clever.

🦶 “Pietre del Bando”: Venice’s Public Announcement Stones

Before newspapers or posters existed, Venice had the pietre del bando — stone blocks where officials stood to read public decrees, taxes, announcements or punishments.

One of the most visible examples is in Campo Santa Margherita.

Crowds gathered around these stones to hear the latest news, delivered loudly by town criers.

It was Venice’s version of a medieval “speaker’s corner.”

Today, they’re a quiet historical trace of a time when public life happened outdoors, in the squares.

🩸 “Ponti dei Squartai”: The Dark Bridges Where Criminals Were Displayed

In several sestieri you can find places once known as “ponti dei squartai” — literally, “bridges of the quartered ones.”

These were points where Venice exposed the remains of criminals who had committed very serious offenses, such as:

- high treason

- murder against state officials

- crimes threatening the safety of the Republic

- political plots

After execution, parts of the body were displayed in specific crossings or elevated passageways to warn the population.

This may sound macabre today, but it was a common medieval practice — Venice simply used discreet, strategic places so the message was clear without disrupting daily life.

Some known zones include:

- Castello (near old administrative paths)

- Cannaregio

- Santa Croce (near the old slaughter area)

- San Polo (close to justice offices)

- Dorsoduro

These sites are rarely marked today, but the names survive in documents and local tradition.

They reveal a much harsher, more complex layer of Venetian justice — one almost never mentioned in standard guidebooks.

👣 Stone Grooves in Sottoportici From Centuries of Wheel Carts

In many sottoportici you can spot narrow grooves or channels carved into the stone pavement.

These are not decorations — they are the result of centuries of carts and barrows being pushed through the passage.

Merchants carried goods from boats to shops along these routes, grinding their wheels along the same lines over and over.

These grooves are literally the scars of medieval Venetian commerce, still visible under your feet.

🏳️ Giudecca Once Had No Active Bell Tower

For a long time, the island of Giudecca (part of Dorsoduro) had no functioning campanile.

Residents relied on the bells of San Giorgio Maggiore, the church that stands across the water.

The sound traveled perfectly over the lagoon, becoming the island’s unofficial clock.

This created a unique rhythm of life where one island depended on another for timekeeping — a quiet reminder of how tightly connected the lagoon’s communities once were.

🚫 Raised Metal Grates Were Early Flood Barriers

Many Venetian doorways have strange metal grates or raised bars at the bottom, often about 30–40 cm high.

These were passive defenses against acqua alta before modern barriers existed.

They kept seawater from rushing into houses and shops during mild tides.

Even today, some of these original grates are still used along with modern removable flood panels.

They are a small but clever example of Venice’s historic fight against the sea.

🍞 “Pan del Doge”: The Luxury Bread Once Reserved for the Elite

The Pan del Doge was a sweet, richly spiced bread made with:

- sugar

- raisins

- candied fruit

- cinnamon and exotic spices

These ingredients came from Venice’s trade routes in the East and were extremely expensive.

For years, this bread was forbidden to ordinary citizens and served only to nobility and high officials.

It was a symbol of wealth, power and the culinary influence Venice held across the Mediterranean.

🧂 Salt Was So Valuable It Functioned as Money

Salt was one of Venice’s greatest sources of wealth.

Imported from Cervia, Chioggia and Dalmatia, it preserved food and enabled long voyages.

It was so precious that:

- it was stored in guarded warehouses

- merchants paid part of their taxes in salt

- contracts were settled using its value

- it became a form of early currency

The Saline (salt warehouses) were among the most strategically important buildings in the Venetian Republic.

Salt literally financed the rise of Venice.

🧱 Muri “a pancia” e “pissotte”: curved walls that hide centuries of clever urban design

In some Venetian calli you may notice something unusual:

a wall that gently swells outward, creating a soft, rounded “belly” shape instead of a straight vertical line.

At first it looks like a construction defect — but it isn’t.

These curved walls appear mostly in narrow, quiet or poorly lit areas, and they served several clever purposes over the centuries.

They are called “Pissotte”

– Built-in system to prevent ambushes

In the past, many calli were dark, especially at night.

A bombed-out wall removed empty corners where thieves or attackers could hide.

By rounding the angle, there was no shadowed space to conceal a person.

It was a simple but effective way to make narrow streets safer.

– Deterrent against nighttime urination

Curved walls also discouraged men from using them as improvised toilets.

On a rounded surface:

- the urine runs off instantly

- it splashes back

- it’s uncomfortable and messy

In other words: you learned the lesson once — and never again.

Many old European cities used similar passive solutions, but Venice preserved them better than anywhere else.

Today, these curved walls are one of Venice’s quietest curiosities — small details that reveal how the city adapted to everyday challenges long before modern urban planning existed.

If you love uncovering Venice curiosities like these, explore also the hidden islands

- 👉 Discover all the islands → 🌊 Venetian Islands – Discover the Lagoon Beyond Venice

- 🚤 Plan your trip across the lagoon → 🚤 How to Get Around Venice

- 👉 Read which are the 🌊 Venice Lagoon Rules — What Visitors Should Know

For further historical details, you can check the official Venice municipality archive → https://www.comune.venezia.it